Talking Justice, the Chinese Way

While restorative justice in China may not always be perfect, it is much more than just an aspiration as it so often is in the West.?

It was a typically hot evening in Kashgar (Xinjiang) last July. There was an altercation in a restaurant located in the inner suburbs. The last man from a table of ten tried to leave without paying.

An argument followed involving the restaurant owner that became a scuffle. The police were called and quickly arrived, three male officers and a woman colleague. They escorted the antagonists outside.

Ten minutes later the restaurant owner, smiling, was sharing the story of what happened. The men at the table had left one at a time, each saying that the others would pay. “It’s not really their fault,” the owner continued, “They’re rural migrants to the city. It’s hard at the beginning. Maybe they can’t afford to pay.”

It is unclear what was said between the police and the antagonists to resolve this dispute to the apparent satisfaction of both parties. What is known is that the Chinese police are experienced in three forms of mediation: people’s mediation, public order mediation, and criminal reconciliation.

Mediation, to borrow the words of Gordon Bazemore, late professor of criminology, Florida Atlantic University, “treats crime as a violation of people and relationships rather than merely a violation of a law.” In Western countries mediation is often termed restorative justice to distinguish it from other forms of justice: retributive justice which focusses on punishment; rehabilitative justice that is concerned with preventing reoffending.

In contrast, restorative justice aims to right wrong and to repair harm in a process that engages offenders and victims meeting together to decide how to make amends. Very often the process is mediated by a third party to ensure that relevant stakeholders are involved, that all parties are empowered, their voices are heard, and that a mutually acceptable outcome is attained.

China leads the world in terms of the scale and diversity of restorative justice programs, according to John Braithwaite, a professor at the Australian National University, Canberra. No wonder, therefore, that British legal scholars were keen to organize an Anglo-Chinese seminar on restorative justice. Joined by colleagues from Beijing Normal University, the Oxford Prospects and Global Development Institute hosted the seminar at Oxford University’s Regents Park College in March.

It rapidly became clear that foundations for restorative justice can be found in the teachings of Confucius. Professor Liu Jianhong, from the University of Macau, explained the centrality of harmony in Confucian thought. In ancient China, restoring social harmony through resolving interpersonal conflict represented the preferred alternative to litigation. Indeed, the Confucian ideal of ‘no litigation’ helps to explain the late development of law in China, with many citizens still turning to mediation ahead of legal redress.

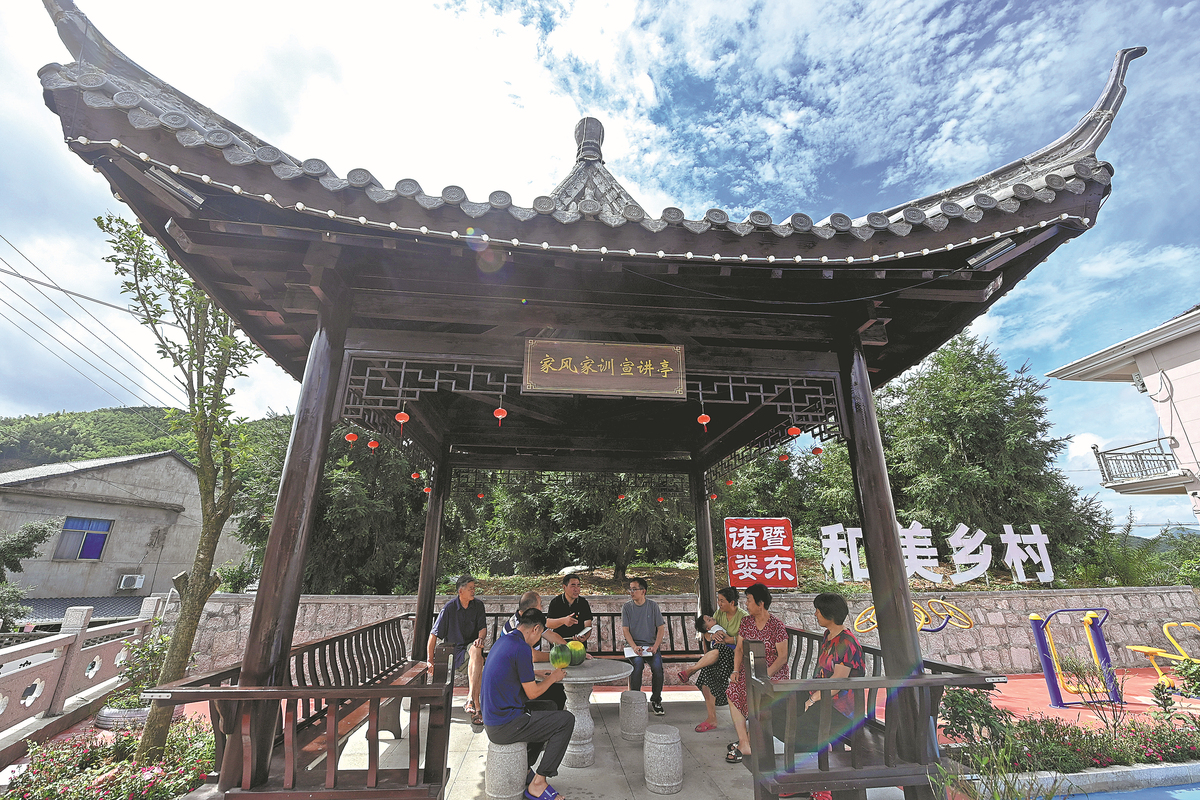

After 1949, informal people’s mediation became a key component in the national “mass line” policy for resolving grassroots conflicts. The tradition continues in the so-called “Fengqiao Model” of conflict management named after Fengqiao township in Zhejiang Province where it was pioneered in 1963. It prioritizes mediation rather than punitive methods when addressing disputes.

In many Western countries, restorative justice is primarily an ideal to aspire to. Where practiced, it is typically voluntarily and used comparatively rarely as an alternative to recourse to law. However, in China, it is supported by government and already operates at scale. There are nearly 700,000 people’s mediation committees with over three million mediators including 410,000 working full time. Some 50 percent of civil cases are resolved through mediation.

There are ways in which mediation in China differs from restorative justice in the West. The fact that it is embedded in Chinese culture, that it is the natural thing to do, can mean that it seems less voluntary than in the West. For Westerners, participating in restorative justice means making an active choice to pursue a novel approach especially in matters involving criminality. Indeed, some Western scholars insist that, if the perpetrator and their victim do not both make a deliberative decision to participate, the resultant process cannot properly be described as restorative justice. The Oxford seminar may have challenged this view.

However, justice itself is also conceptualized in different ways. Western justice refers to universal principles that are independent and separate from government, so-called natural justice. In China, law is seen as an expression of the intentions of the state that are understood always to be in the best interests of the people. It is, therefore, expected that the state will play a central role in mediation. Hence, the three million approved mediators mean that the state is present in much Chinese mediation but seen as a benign constructive influence not as a coercive force.

Restorative justice can be translated in complementary ways in Mandarin, both as sifa (adjudication) and as zhengyi (justice). Therefore, as Professor Zhang Qi (Peking University) explained in Oxford, mediators, in seeking positive outcomes for all parties, are likely to participate in adjudication if the protagonist themselves cannot admit to blame or hurt. In the West, both parties would generally need to recognize themselves as perpetrators or “victims” before the process of restorative justice could proceed.

The potential for cultural misunderstanding is illustrated by the Western response to the celebrated film, The Story of Qiu Ju, directed by Zhang Yimou, and released in 1992. Qiu Ju and her husband grow chili peppers in their village in Shaanxi Province and are refused land on which to build a shed to store them by the village head. A confrontation results in Qiu Ju’s husband being kicked in the groin. Qiu Ju demands an apology and, when not forthcoming, she seeks justice for what she believes is an abuse of power.

Heavily pregnant, Qiu Ju travels to county, town, and eventually to the provincial city with benevolent officials in each place seeking to mediate but never to her satisfaction. Eventually she has recourse to law, but the outcome is not the apology she desired. Instead, the village head is imprisoned on the very day that she had invited him to join celebrations for the birth of her daughter.

Western critics, such as Geor Hintzen, lambasted Zhang Yimou for his portrayal of Chinese officials as being well-intentioned, failing to appreciate their training in mediation techniques, and the positive expectations of the state that continue to be prevalent in China.

Returning to restorative justice and the police, the ethos of policing in China still echoes “mass line” principles developed after 1949. These envisaged the police working closely with neighborhood committees to maintain a deep relationship with the people who would mobilize to prevent crime. Today, policing is shaped by the motif of “Four HAVEs and Four SHOULDs”: police should respond to emergencies people have, help with difficulties they have, rescue them from danger and meet any needs that they have. This means that, if asked, the police may participate in people’s mediation, but mostly they are engaged in public order meadiation and criminal reconciliation.

The former should be viewed in the context of China’s pursuit of social harmony; police can host mediation if disputes violate public order, and the adverse effects are minor. Mediation in these cases has a predominantly social function, avoiding disharmony, whereas restorative justice in the West is designed primarily to benefit the individuals directly involved.

Criminal reconciliation began with legislation in 2008 and relates to civil disputes or negligent crimes that carry the possibility of imprisonment for up to three and seven years’ respectively. According to Professor Yan Zhang (University of Macau), Chinese police officers, as members of a culture influenced by Confucius, are often predisposed to mediation in marked contrast to police in Western countries. The latter, Professor Kerry Clamp (University of Nottingham) characterized at the Oxford seminar as being trained to “catch and convict.” Professor He Ting (Beijing Normal University) emphasized the importance of mediation in China’s youth justice system.

However, there are very few police officers in China – about 12 per 10,000 population compared to a global median of 30. Consequently, under pressure, police may engage in mediation to avoid lengthy court hearings. Similar pressures may mean that mediation focuses on determining the sum of compensation acceptable to both parties although, as in the case of Qiu Ju, it is not always money that is needed, sometimes it is an apology or simply understanding. On occasion, too, mediation may be neglected. Examples include when local management targets prioritize prosecutions or when it is considered important not to set a precedent.

While restorative justice in China may not always be perfect, it is much more than just an aspiration as it so often is in the West.?

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +